Overly Concentrated

Illustration by Ayo Arogunmati

I take a walk each morning, starting from Lillian I head west to Yonge then south to Davisville and back north to Lillian. The entire trip takes me an hour but before I get home, I stop by a coffee shop, owned by a pleasant Turkish family, to buy a coffee with one sugar and milk [1]. I pay three dollars and fifty cents for one cup and if I want a second cup, I pay the same price as the first cup. This exchange between me and the coffee shop is what would be considered a direct relationship between the price of an item and the quantity you get. If a graph of this relationship is plotted with the quantity on the horizontal axis and price on the vertical axis, it would be a line upward and to the right. The more I buy, the higher the total cost. Physical items display this direct relationship unlike digital products that tend to have a less direct relationship between price and quantity.

When compact discs and cassettes were used for storing movies and music, the relationship between price and quantity was still not linear. After buying the CD or cassette, I own it and I could continue use it until it stops working. The axis of the graph of this relationship would be similar to the coffee purchase but the slope will be steeper with a high price for the first use of the disc and would drop faster for each additional use [2]. Now that streaming is the best source for finding and listening to music or watching movies, the quantity sold, and the price paid is even more less direct. This relationship is forcing artists to find new ways to monetize their music rights before the industry power dynamics shifts further away from the artists [3].

Popular artists are selling their song catalogs to music investment funds and many observers are confused by this decision. Terius Nash, better known as The Dream, was one of the first artist to sell a vast number of his songs to Hipgnosis Music Fund. He sold 300 songs in total with many of his top selling and charting songs included in the package [4]. Assuming he owns 100% of the rights to these songs, why would he decide to sell them to an investment fund? Is he not supposed to retain his master rights for future generations? And why seek liquidity at such a young age? [5] These are all valid questions and can best be answered by The Dream, but like any investment even music rights, being overly concentrated in one asset class increases the chance of an unexpected loss of value.

If you had an option to get money now or over a period of time which of the two options would you choose? My choice would depend on the assumptions I make about the present value of the money to be received. Investors face this issue when they own one type or a few types of assets that have a high concentration in their portfolio and they find it hard to monetize these assets. Stock options granted to C-level management, real estate and private business ownership are three assets that tend to have a high concentration characteristic in a portfolio. Song royalties tied to a songwriter’s intellectual property rights also face similar frictions. But while there are strategies in place to address the former types of asset, royalty rights operate in a muddier environment compared to the other assets [6].

Before trying to make sense of why artists are choosing to sell their song catalogs, we need to understand exactly what the purpose of an investment fund is. An investment fund is in business to generate a return for its investors. Hipgnosis is the biggest player in the acquisition of song catalogs. It was created in 2018, raising GBP 1 billion to buy copyrights directly from song writers and producers*. The amount of money paid by Hipgnosis for song catalogs has led to public skepticism of the fund because they are seen as investors who are distorting the fair value of these royalties. There’s even more criticism for purchasing catalogs from black artists who have historically had to fight to retain their ownership. Likewise, black artists are also being criticized for selling their rights to Hipgnosis. But this criticism is unnecessary because a fund like Hipgnosis improves valuation transparency, and liquidity in a market that is highly illiquid for artists.

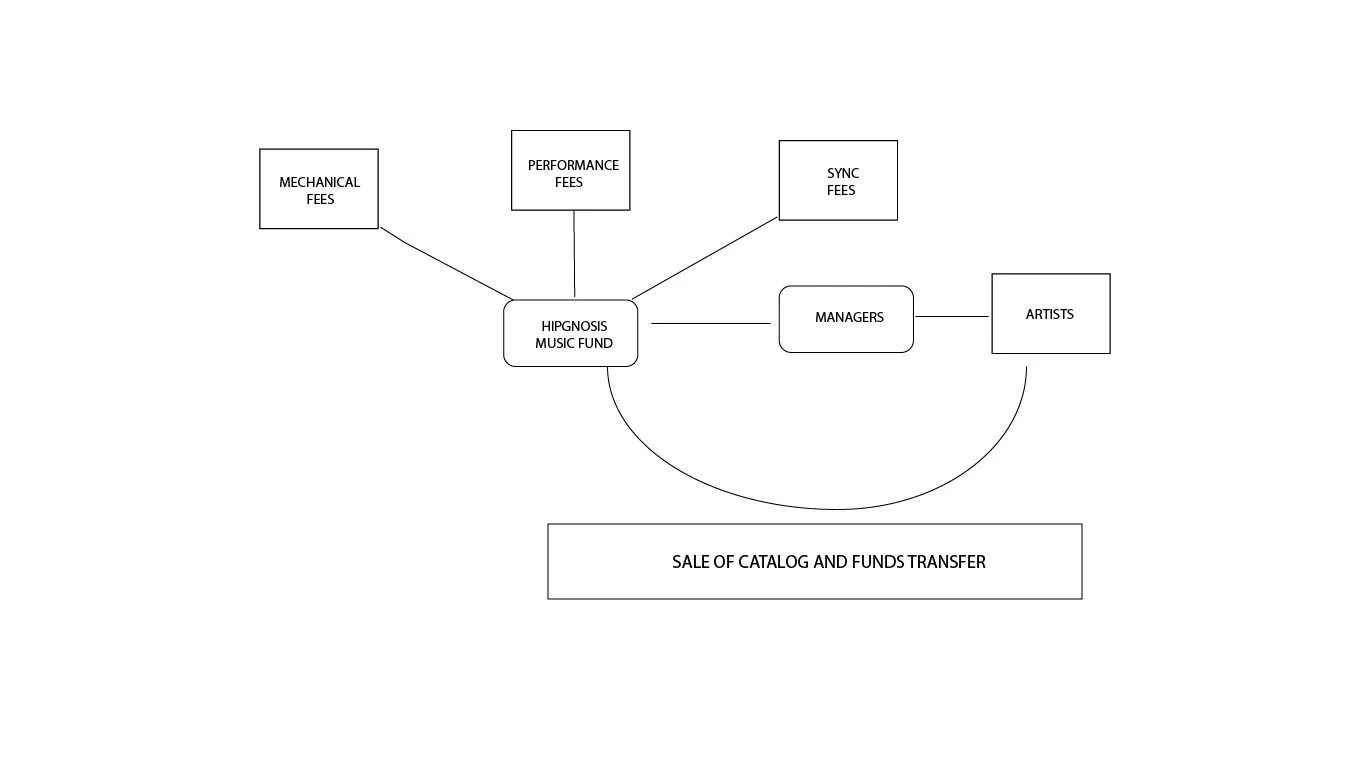

Simplified Royalty Structure (pre-Hipgnosis)

Hipgnosis was founded by Merck Mercuriadis with an objective to provide shareholders with an attractive and growing income, including capital growth in the asset base by investing in songs and musical intellectual property rights from performance royalties, mechanical royalties, and synchronization royalties. The company wants 100 percent interest in the songwriter or producer’s rights in each song. As of March 2020, the company had 54 catalogs and 17,000+ songs under management and generated GBP65.7 million*.

Hipgnosis has noted several factors that supports its investment thesis including 1) the movement of customers to streaming through digital distribution platforms like Spotify, 2) available songs to purchase due to higher levels of piracy, and 3) artists trying to find new ways to address estate and tax issues*. Hipgnosis claims to be led by a team of knowledgeable music insiders to improve song management and cost efficiency in the collection of royalties.

Simplified Royalty Income Structure (post-Hipgnosis)

There are two key questions in establishing a relationship with a fund like Hipgnosis. An artist needs to determine if their catalog meets the investment criteria for Hipgnosis and they need to determine how much to sell their catalogs for.

According to Hipgnosis annual report, the company’s goal is to seek artists that are [7]:

High profile

Artists well known to society

Culturally influential artists: 1) typically, continuously played over time and 2) Often with enduring appeal that attracts covers from new recording artists

With a track record of producing predictable and reliable income

Uncorrelated to global capital markets

The Hipgnosis investment criteria is for the seasoned artist that is not necessarily retired but has spent sufficient time in the music industry to have some critical acclaim. Hipgnosis wants artists that are top selling, Grammy nominated and Billboard charting song writers and producers. The Dream was the first artist I heard of that sold his catalog to Hipgnosis. He appears to be the perfect candidate to hold as a portfolio name for Hipgnosis because he meets the investment criteria laid out in their annual report.

Before going deeper on how artist can value their catalog, the terms need to be defined. Concentrated assets are interests through ownership for a long period of time that has appreciated in value. The cost is lower relative to the current market value of the asset [8]. People who have concentrated assets are often seeking a reduction to the risk of the asset, generate liquidity to diversify, meet their spending needs or to optimize their tax efficiency. These assets have significant capital gains buried in the asset and are difficult to sell without giving a discount to an interested buyer.

The uncertainty around consumer choice as it relates to music consumption is the one of the factors that has limited the predictability of music royalties. This lack of predictability and sustainability of royalties in the industry is why Hipgnosis is important in its role similar to a market maker in the financial markets.

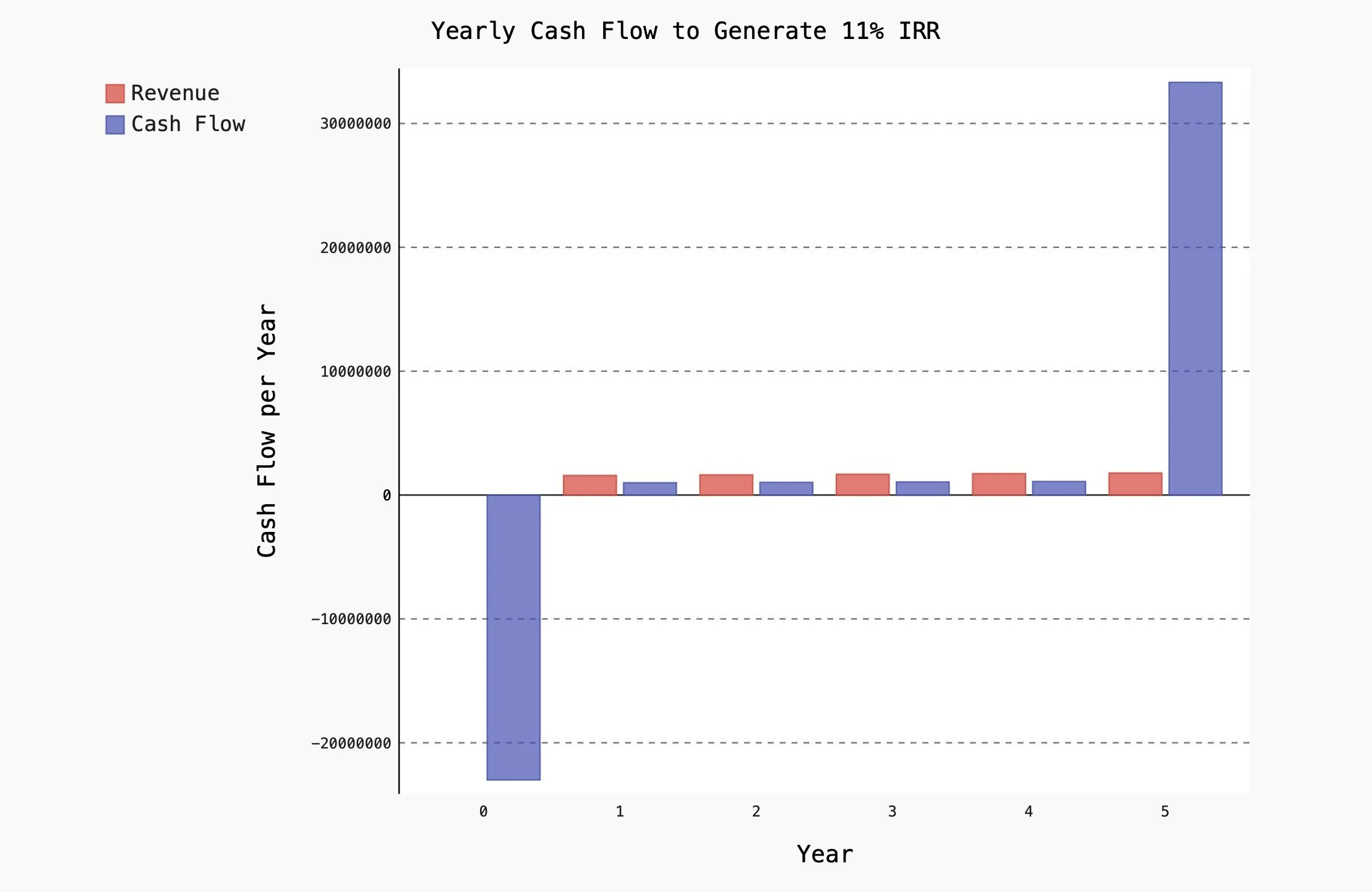

I decided to use The Dream’s catalog sale to suggest how an investor might approach the valuation process for the catalog acquisition. Likewise, an artist can use this method to evaluate whether the price paid is sufficient for them to give up their rights in a sale process. The key decision tool is to determine the internal rate of return realized over a specified investment period [9].

The key assumptions I made are reflected in the table and if you are interested in visual display of the cash flows over the five (5) year investment period, you can click here for an interactive version or click the cash flow projection chart.

Assumptions and Income Model

I calculated an internal rate of return of 11% for the five-year investment period for an investor. The vast portion of the cash flows is realized in the fifth year by the investor as this is the terminal year of the investment. The drivers of the returns include the exit multiple of 20 times and the revaluation that occurs over the last four years of the investment.

If an artist determines the IRR that is likely to be realized by an investor, the artist may decide not to sell. On the other hand, the upfront cash provides an artist with liquidity but with the additional issue of how to allocate the money from the sale.

NOTES

[1] Lactose free only

[2] The graph of this relationship would be downward sloping. The more consumption the less it costs per consumption

[3] The music business has several stakeholders including the artists, record labels, distribution companies, and performance venues. Over the last two decades, many of these stakeholders have increased their structural power through acquisitions and mergers. The one party that has failed to consolidate are the artists who remain fragmented. For example, Universal, Warner and Sony are the only three remaining record labels including ownership of subsidiaries that have their own subsidiaries. Moreover, distribution channels like Spotify and YouTube have also grown exponentially in market power because of the low competition that they face. The effect of the power concentration is that royalties received through Performing Rights Organizations (PROs), mechanical and synchronization rights flow mostly to the record labels and streaming companies. Live performance and ticketing also have concentrated players like Ticketmaster and Live Nation. Because of the pandemic new capital is now available to buy out independent owned venues across the US, further consolidating the power of the key industry players. Monopoly power tends to breed new monopolies in the industry structure and the creation of Hipgnosis might be a direct response to the increasing power of record labels, distribution channels and performance venues in the industry.

[4] This is as reported by Hipgnosis annual report, includes songs such as Justin Beiber “Baby”, Mariah Carey “Touch My Body” and Beyonce “Single Ladies”. The Dream sold 75% of his interest in his song catalog for $23 million according to reports

[5] This is only speaking of The Dreams actual age not as a musician with years of experience

[6] Some of the strategies for other more common types of concentrated assets include outright sale, loans against the value of the equity and estate freeze

[7] Market value is not fair value. Market value is the exchange price for an asset between two parties, while fair value is the intrinsic value of the asset

[8] The investment criteria are as reported by Hipgnosis annual report. The criteria is geared towards more established artists. This sets Hipgnosis more as a private equity style player than a venture capitalist

[9] The IRR is used by investment funds to evaluate the return on their investment. It is the steady state compounding rate that would take a value today and arrive at a future value over an investment horizon

[*] Per annual report